When you think of the proverb “Too many cooks spoil the broth”, it’s typically about chaos in the kitchen. But believe it or not, it also has a lot to teach us about rock bands. One of the best examples? Genesis.

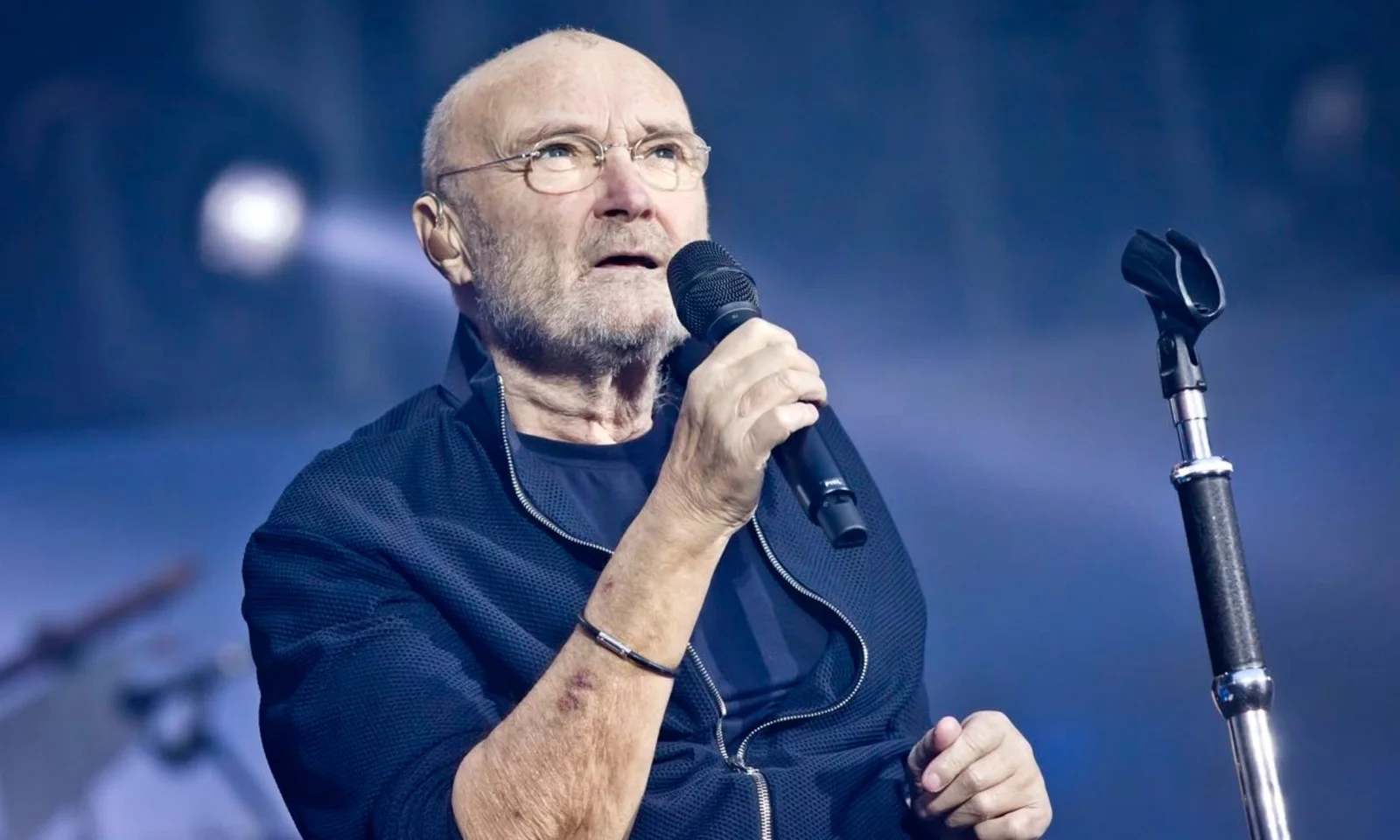

Phil Collins: the songwriter-in-waiting

Long before Phil Collins became a global superstar, he was quietly scribbling songs in his room. His ambition was clear: writing songs, creating melodies. Even if most of those early attempts never saw the light of day, they built a foundation for his later success — both with Genesis and as a solo artist.

However, when he joined Genesis in 1970 (initially as drummer, later becoming lead vocalist), he recognized something important. Genesis already had its main songwriting triumvirate: Tony Banks (keyboards), Mike Rutherford (bass/guitar) and Peter Gabriel (vocals/flute) in the early part of the band’s life. Phil understood that if he pushed himself into that songwriting role too soon, friction could result. Indeed, in a 2014 interview he said:

“The spirit of Genesis was Tony, Mike and Peter… I didn’t regard myself as a songwriter then. But there were things in Genesis I was highly influential in. My strength was arranging.”

Louder

He adds how he was “very into the first line‐up of Yes … I remember listening to them … and loving the way they took other people’s songs … and did something different with them.”

Louder

In short: Collins kept his head down, focused on his strength (arrangements, outside connections) rather than blitzing ahead as another songwriter. He still had big ambitions — but he picked his moment.

When a band has too many voices

While the band had great talent, that very fact caused some internal tension. With four or five strong creative minds all vying for input, things got complex. One vivid example came from Steve Hackett (guitarist, who joined Genesis in 1971). On the album Selling England by the Pound (1973), Hackett revealed:

“I had to threaten them to get ‘After The Ordeal’ on the album … If they weren’t going to include all of my ideas … I was off.”

In fact, “After The Ordeal” is an unusual track: a four-minute instrumental without the repeating hook that pop audiences often latch onto. On first listen it might feel meandering — but it’s also a real show-piece of the band’s musicianship, and Hackett forced its inclusion.

The message here: when everyone has ideas, and when some ideas feel “outside the expected”, conflict is likely. The album itself has been called “the one to encapsulate what Genesis did best” by Hackett.

What went wrong (and what went right)

So, does the adage hold? In a way, yes. Too many cooks can spoil the broth — if not managed well. Here’s how the dynamic played out in Genesis:

Strength in diversity: The band had multiple talented songwriters, instrumentalists, and arrangers. This allowed them to create ambitious, varied music (long pieces, concept songs, risky instrumentals).

Weakness in coordination: Multiple voices meant competing ideas, possible resentment or sidelining. Hackett’s “I’ll leave if you don’t include my track” is emblematic.

Timing of contributions matters: Collins’s decision to initially step back from songwriting and focus on arranging helped smooth things — and later, when he found his voice, the band benefited.

Clear leadership (or lack thereof): With no single strong “band leader” to arbitrate, negotiations were sometimes fractious. The cooking recipe needs a head chef; otherwise you get too many people adding salt.

The right moment for change: Ultimately, Hackett left Genesis (in 1977) because he felt constrained: “There was an aspect of claustrophobia … Genesis was becoming a little bit too much of a closed shop.”

Why the broth still turned out great

Despite the conflicts, Genesis made some truly extraordinary music. The album Selling England by the Pound is often held as a pinnacle. In his interview, Hackett says:

“Selling England is the album I’m proudest of in Genesis … for its unique quirkiness.”

And their ability to balance ambitious prog ideas (long pieces, multiple movements) with accessible songwriting (e.g., “I Know What I Like”) is part of what made it endure.

Lessons for bands (and maybe life)

Know your role: Just as Collins recognised his strength in arranging rather than immediately being the chief songwriter, people in any group benefit from recognizing what they bring best.

Manage voices: A team with many strong voices can be powerful — but without coordination it becomes a cacophony. Someone needs to steer or decisions need clear resolution methods.

Pick your battles: Hackett picked the battle to include “After The Ordeal”. That worked for him in that instance — but it also strained relationships. Choose when to push and when to collaborate.

Allow for evolution: Collins evolved into a songwriter; Hackett eventually needed to leave. Growth often requires change.

Celebrate the chaos — but organise it: Genesis turned what could have been chaos into creative gold by harnessing the multiple voices, though not without friction. The eclectic mix is part of why their albums still resonate.

Final thought

So yes — too many cooks can spoil the broth. But if the cooks know what their roles are, communicate, let one take the lead when needed, yet still keep a lively, creative kitchen, the result can be brilliant. Genesis may have had the tension, the many voices, the internal negotiations — yet the music they produced is proof that sometimes a crowded kitchen, well-managed, can cook up something extraordinary.