Every drummer speaks with a voice of their own once they sit behind the kit. Even when raised on the same records, each player forges a rhythm that’s distinctively theirs.

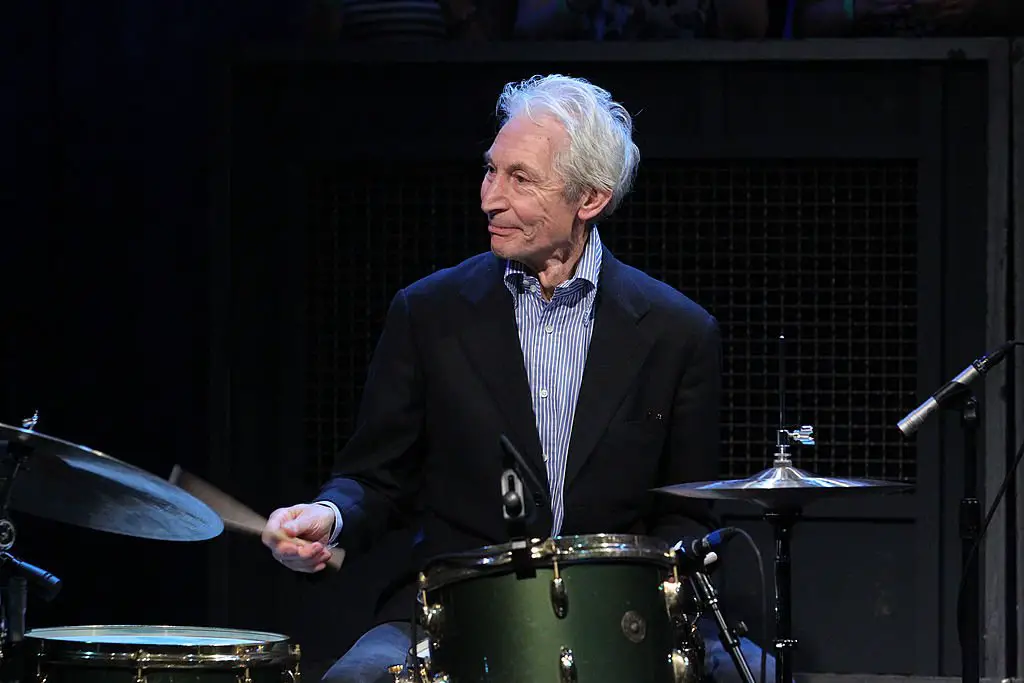

Charlie Watts of The Rolling Stones understood his irreplaceable role, yet he held immense admiration for Tony Williams—a drummer whose touch carried a brilliance that simply couldn’t be duplicated. Unlike many of his peers, Watts didn’t approach every performance as a showcase of power. Instead, he played with intention, serving the song rather than overshadowing it.

Though some Stones tracks demanded raw speed and drive, Watts often locked in with Keith Richards’ guitar, building grooves that perfectly supported the riffs. That sensitivity came from his jazz roots, long before rock and roll dominated his career. For Watts, the magic wasn’t about stealing attention but about elevating the whole band.

Still, when the music called for fire, Watts delivered. On tracks like Paint It Black, his explosive fills cut through the mix, pushing the band’s chaotic energy to new heights.

Yet for him, Williams embodied a different level of artistry. While Buddy Rich stood tall as a powerhouse of jazz drumming, Tony Williams dismantled conventions and reshaped how rhythm itself could be heard. Many jazz drummers of the era stuck to the straight and narrow, but Williams brought a fluid swing that injected fresh life into every performance.

Miles Davis and other jazz giants thrived on harmonic changes, but when Williams laid down a groove, he transformed the entire feel of the music. Watts marveled at this, acknowledging that no drummer—even at the height of The Stones’ fame—could rival Williams’ daring style.

Williams’ genius lay in his unpredictability. Where others played steady and predictable, he shifted dynamics, altered time signatures, and even used his left foot to bend rhythm in ways no one had imagined. “Nobody played like Tony,” Watts reflected, pointing out how Williams could fracture time or cut it in half with ease—a skill few drummers ever mastered.

That kind of groove seeped into Watts’ own playing. The Stones often thrived not on flashy fills but on the tension of holding a riff steady, subtly shifting the rhythm, and letting the swing carry the song. Even when the band projected danger and rebellion, Watts recognized that the effortless shuffle Williams pioneered had a deeper, lasting impact.

Playing what’s written might keep time—but making it swing turns a song into history. That was the lesson Watts carried with him, even as he became the steady heartbeat of one of rock’s most legendary bands.