You might know “Alabama Song (Whisky Bar)” from The Doors. But long before that, its roots were planted in the late 1920s Germany, in a theatrical and political world you’d never expect in rock history.

The words began life as a German poem by Bertolt Brecht in 1925 (later collected in Hauspostille). Because Brecht wasn’t confident in his own English, the poem was translated into quirky, broken English by his collaborator Elisabeth Hauptmann.

Then Kurt Weill, a composer with a flair for mixing genres, set that text to music in 1927 for a small theatrical piece called Mahagonny-Songspiel (or Little Mahagonny).

A few years later, Brecht and Weill expanded that idea into a full opera, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (in German: Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny), which premiered in Leipzig on 9 March 1930.

In that opera, “Alabama Song” is sung — in English, even though much of the opera is in German — by Jenny and others in Act I, as they journey toward Mahagonny, a mythical city of excess, pleasure, and moral unmooring.

Musically, the opera is eclectic: ragtime, jazz, counterpoint, cabaret, even ironic touches. It’s meant to jar, to provoke.

Because of its biting critique of decadence, capitalism, and social decay, Mahagonny was deeply controversial. After the Nazis came to power, Brecht and Weill’s works (including this one) were banned.

The Doors Find the “Whisky Bar”

Fast forward to the 1960s in Los Angeles. The Doors are playing clubs, experimenting, searching their voice. Keyboardist Ray Manzarek reportedly revealed to his band a record he had of the Mahagonny piece — and they decided to adapt “Alabama Song” into their repertoire.

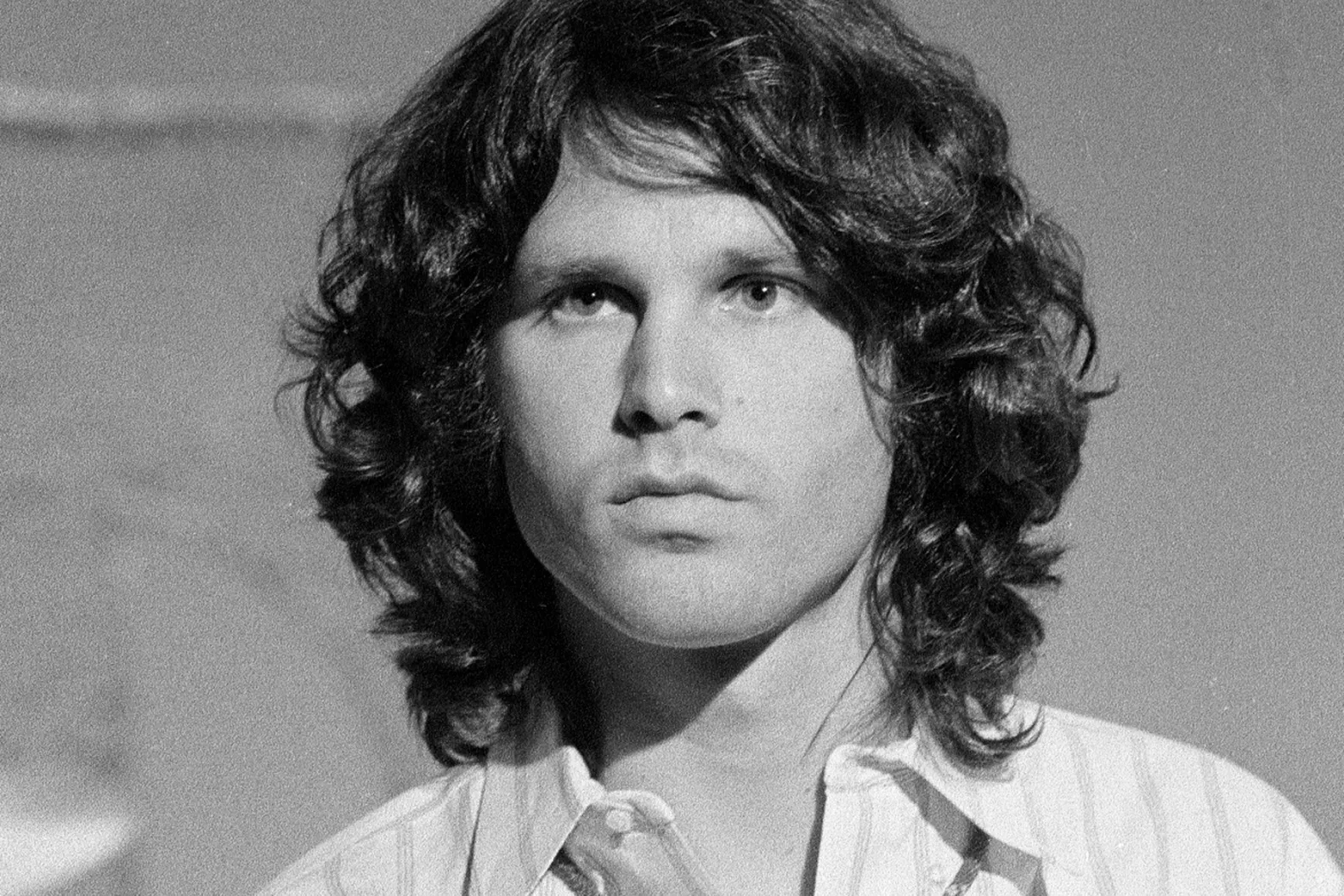

The Doors’ version appears on their 1967 self-titled debut album, released when Morrison was barely 23.

They preserved much of the original lyric — except for one notable change: where the original says “Show us the way to the next pretty boy,” Morrison sings “Show me the way to the next little girl.” That twist gives the song a darker, more ambiguous edge.

Another striking element: Manzarek used a marxophone (a zither-like instrument with hammers) to add a jangly, carnival-like accent to the track. He claimed he had never heard of that instrument until producer Paul Rothchild suggested it — but it fit perfectly.

In the live years, “Alabama Song” became a stage favorite. The Doors even mashed it with Back Door Man and Five to One in concert, pushing into chaotic, improvisational territory.

Interestingly, “Alabama Song” might have been one of the deciding factors in Elektra Records signing The Doors. Label execs were impressed by the band’s willingness to reach into musical history.

Medium

Themes, Parallels, and Morrison’s Mirror

At its core, “Alabama Song” is a dark anthem of pursuit — of pleasure, escape, desperation. In Mahagonny, the city is a playground without limits, but with fatal costs. The opera hints that indulgence at any price leads to collapse.

Jim Morrison, in his life and myth, lived such contradictions. Excess, self-destruction, poetic longing — his path mirrors some of the opera’s warnings. His famous line — “I believe in a long, prolonged, derangement of the senses in order to obtain the unknown” — feels like it could have leapt right from Brecht’s world.

When Morrison sang “whisky, whisky all the time,” it felt less like a cover and more like confession — binding himself to the operatic desperation, channeling old paths through a new, electric darkness.

Later, other major artists picked up the torch. David Bowie, himself a fan of Brecht, performed “Alabama Song” live during his 1978 tour, reintroducing it to a new generation.

Covers abound: Nina Simone, Marianne Faithfull, The Young Gods, Marilyn Manson, Ute Lemper, among others. Yet none has quite captured the haunted, borderline-sacramental feel of Morrison’s version intertwined with operatic ancestry.

In 2000, The Doors resurfaced for a VH1 Storytellers special, with Ian Astbury stepping into Morrison’s role. “Whisky Bar / Alabama Song” was among the tracks chosen, and Ray Manzarek recounted how and why they first embraced this strange opera gem.

Why This Strange Journey Matters

What makes “Alabama Song” so compelling is that it connects very distant worlds: Weimar-era German theater, radical musical experiment, and 1960s psychedelic rock. It shows how subversive art can echo across time.

And in Morrison, we see something of the opera’s stars: individuals drawn to excess, to boundary pushing, to fragmentation. The song becomes a bridge — between the German avant-garde and American rock, between theatrical satire and lived tragedy, between decadent fantasy and haunted confession.

Next time you hear “Show me the way to the next whisky bar,” maybe imagine Jenny stepping toward Mahagonny’s broken neon lights. And maybe you’ll catch a glimpse of Morrison’s silhouette in the smoke.